While the Roman Empire has influenced us in many ways, one of its most popular concepts is the gladiator. Gladiators were a societal caste of warriors, and are famous for fighting each other, often to the death. Modern stories have a lot of notions about what makes a gladiator a gladiator, and many of these are true. But there’s more depth and nuance than one might expect. This is what gladiator life was really like.

The People Who Would Become Gladiators

In Roman society, there were strict cultural rules about who could become a gladiator. The first recorded gladiators were prisoners who surrendered to Rome during wars. The Romans viewed soldiers who surrendered very negatively; the soldiers were viewed as having forfeited their lives. They were given the opportunity to atone for their sacrificed lives by fighting as gladiators. These prisoners fell into three major groups: the Samnites, the Thracians, and the Guals. Among the gladiator population, most of them were Samnites. They were known for their heavy armor and fancy helmets, which eventually became the key traits of the gladiator class called Secutor. The Guals were eventually absorbed by Rome, and became the murmillo gladiator class.

There were plenty of native Romans who became gladiators as well. Many gladiators were criminals. Not just any crime could lead to a career as a gladiator. Those crimes included banditry, theft, arson, treason like rebellion, tax evasion, and refusal to swear oaths. If a crime was seen as particularly obnoxious to the state, those criminals would receive more humiliating and harsh punishments in the arena. Both criminals and captured soldiers would be branded with tattoos. These tattoos could be on the face, legs, and for soldiers specifically, the hand.

Finally, some people were paid volunteers. Volunteers accounted for around half of all gladiators, and they tended to be the more well-trained ones. These volunteers were, in most cases, poor or non-citizens; these people enrolled for consistent food, housing, and a chance at gaining fame and fortune.

There were some circumstances that would lead to non-traditional gladiators entering the arena. There were some female gladiators, but they were often ridiculed as absurd by their audience. High-class citizens were generally forbidden from becoming gladiators, but there were a few notable exceptions. One extreme case was the Roman Emperor Commodus, who frequently fought in the arena. However, he and his opponents would only use wood swords, resulting in bloodless battles. Commodus would win all his battles, and on other occasions, he would even fight beasts like lions and ostriches.

How Gladiators Fit Into Their Society

Gladiators were considered the lowest rung of Roman society. They were commonly despised by the general population. As most of them were slaves, criminals, or soldiers, they did not have much standing. When someone becomes a gladiator, they essentially sign their lives away to their managers. By signing with these managers, the gladiators are considered sentenced to death. They could not vote, they were unable to leave a will or plead in court, and were possessions of their masters. A sympathetic master might grant some leniency to their gladiators, but this was not to be expected. ladiators were educated in harsh conditions apart from commoners, and they were socially and even physically separated.

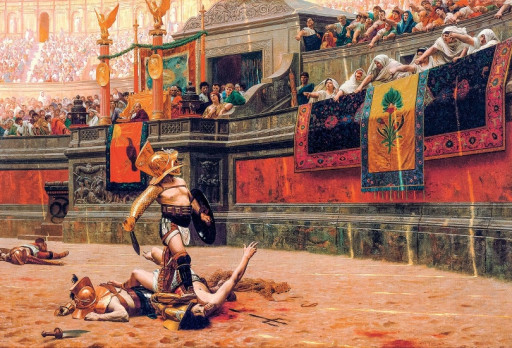

Despite their status as outcasts, gladiators were wildly popular. Gladiators who fought bravely and skillfully would become fan favorites, similar to modern sports stars.. Gladiators were discussed widely, even as the subject of great works of art. Epic matches would be immortalized in sculpture or painting, including portraits of the combatants.

The night before a day of gladiatorial games, gladiators were given their last meals. These meals could be public or private, and were the place for them to say goodbye to their family and put their business in order. When these goodbyes were made public, they would be viewed by audiences of interested fans. Some were even publicized and marketed to increase interest in the games.

Training a Gladiator

School was the starting point for gladiators. These schools were frequently run by gladiator families, which would likely include several retired gladiators to serve as teachers. These gladiator families were also considered extremely low in society, on the same social level as butchers or pimps. But high class families with popular gladiators might not face any social stigma.

Most of these schools were privately run. A revolt occurred in one private school, known as the Spartacus revolt. This rebellion was very difficult for Rome to handle. After a series of costly, bloody, and disastrous campaigns by Roman troops, it was eventually suppressed. Once the rebellion was over, the Roman state issued stricter rules for gladiator schools. The Roman state also feared that private schools would lead to private armies for the rich. These two factors led to the state absorbing more and more gladiator schools over time, until they were all state-run.

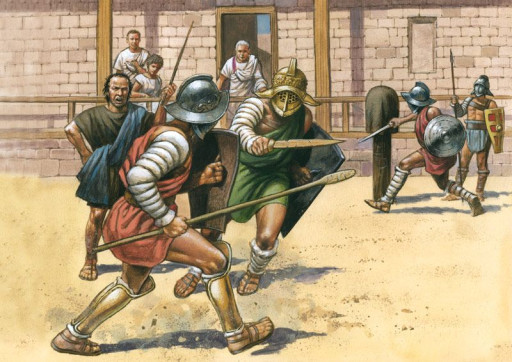

Volunteers needed permission to join a gladiator school. If they received permission, then they would be assessed by a physician. This assessment would result in the terms of their contracts, which included how they would perform, their style of combat, and how they would be paid. Finally, the gladiator-to-be would take a sacred oath. Then, they would be trained by retired gladiators in specific styles. In school, these training gladiators could ascend to different grade levels. All combat within the school was nonlethal, as students were required to use blunt, wooden weapons. Gladiator training also included mental components, like being stoic and unflinching even in death. Left-handed gladiators were given special training in order to fight right-handed opponents. This often gave left-handed gladiators an advantage, as they had extra training and an unorthodox fighting style.

Life Built Around the Arena

Once a gladiator had completed training, they were ready for the arena. Most gladiators fought 2-3 times per year, and would frequently die before they reached 10 battles. One gladiator was recorded to have survived 150 matches and died at age 90. But the average lifespan for a gladiator was 27 years old. It was noted that for every 100 people who entered the gladiator arena, 19 would die. Those who died were likely early in their careers, ranging in age from 18-25 years old. Over time, the death rate rose from 1 out of 5 to 1 out of 4, thanks to mercy being granted less often. At the height of the Roman Empire, there were roughly 400 gladiator arenas, which included 8000 deaths a year from gladiator execution, combat, and accidents.

Gladiators would be housed close to the arena. Their living quarters were cells arranged in barrack formations. These living areas were strictly segregated by type of gladiator and status. Any potential opponents were kept separate and safe. The discipline for these gladiators was brutal, sometimes even fatal. During Rome’s early days, arenas would house around 15–20 gladiators. Eventually, they would expand to around 100. There would be a small cell for punishment, not large enough for the gladiator to even stand.

While the discipline was harsh, the gladiators were well cared for. Arena officials had spent a lot of money to create popular gladiators, and they didn't want to harm them unnecessarily. The gladiators were fed a high-energy vegetarian diet that included barley, boiled beans, oatmeal, ash, and dried fruit. Barley was considered inferior to wheat, but was also seen as something that helped strengthen the body. This led to gladiators frequently being called barley-eaters. Gladiators were also regularly massaged and given high quality medical care.

Not much is known about the religion of gladiators, but murals frequently depict the goddess Nemesis. It is believed that gladiators worshiped her, since she represented fortune and karma.

Setup for the Games

The games were ready to begin. These games lasted around one to three days, and were often held in honor of important political figures and their families.

The day would begin with a procession entering the arena. They were followed by a small band of musicians, playing fanfares on their trumpets. The trumpeters were followed by people holding images of the gods, who were asked to witness the proceedings. Next, a scribe would enter to record the outcomes of the matches, and then a man carrying palm branches. These branches would be presented the victors as an honor. Finally, the editor– the person in charge of the games– entered. The editor arrived with a retinue carrying all of the gladiators' equipment, armor, and weapons. And lastly, the gladiators would enter.

The first events featured the beast hunters and beast fighters. Many of these fights were essentially executions, as these fighters had almost no chance of surviving. The battles with the beasts were followed by actual executions. After that, some gladiators would stage Greek or Roman myths or historical reenactments. These reenactments included the actual deaths of proper players, making these dramatizations another form of execution. These were made as punishments for particularly unfavored criminals, but were assigned as appropriate given their crime. Sometimes, gladiators would be executioners, but they generally preferred a fair fight. If the punished prisoners put on a good show and became respected, they had a chance of actually surviving. Even fewer of them became proper gladiators.

The day of games included some comedic fights as well. While these fights were meant to be over-the-top and parody the regular fights, they could still become lethal. These would include burlesque musicians who were dressed up as animals. Some people would even be decorated in feathers, jewels, or precious metals.

Meanwhile, the gladiators would practice in warm-up matches. These would be strictly monitored by the editor to ensure all weapons were blunt and no gladiator was injured.

The Combat

Finally, the gladiators arrived for real combat. They could be facing anyone, from other gladiators to condemned criminals to animals.

Many matches had been designed to pair different types of gladiators against each other to help maintain audience interest. Some gladiators would be slow and heavily armored. Others were more nimble and tired less easily. Some gladiator classes were considered “fantasy” types, where gladiators were given themes. The retiarius, a fighter themed after a fisherman, is one example of this. The retiarius would fight with a weighted net and a trident, both typical tools of fishermen. Other styles of combat included cestus fighters (which were essentially boxing matches), chariot battles, and horseback fights with archers. These matches typically lasted 10-15 minutes, with rare ones lasting 20. There would be about 10-13 matches a day, one at a time.

These fights were tailored for audience preference. Generally, the audiences preferred to watch the highly skilled gladiators fight in relatively even matches with complementary fighting styles. These types of battles were the most costly, as these gladiators were expensive to hire and train. A much cheaper option was a general melee, with a group of lower skilled fighters. While they were cheaper, they were also less enjoyed.

While typical matches were one on one, sometimes the winning gladiator would need to immediately fight a new foe. This third gladiator, the tertiarius, was well rested and therefore provided a new level of challenge. The teriarius were generally sent in on the whims of the editor, and were used as an unexpected extra for audience appeal. These battles were more prolonged and bloody, which usually made the victor of round one reluctant to fight a new gladiator. If the old fighter stalled, he would be whipped or poked with hot irons until he engaged his new opponent. Generally, the gladiator would not survive fighting a well-rested opponent, but occasionally a highly skilled fighter could manage.

When both gladiators were trained and experienced, the editor might try to add stagecraft. Battles could be accompanied by music during interludes, or even during the actual fight. The musicians might build up a frenzied crescendo during the round, or blows might be punctuated by blasts of the trumpets. In the best matches, bravado and skill were more important to the audience than bloodshed. Some gladiators could even make careers out of bloodless victories.

Trained gladiators were expected to follow the rules of combat. To help facilitate this, a referee and assistant would be on the field alongside the gladiators. These arena officials would have long staves to separate or caution gladiators at crucial points. The arena workers were frequently retired gladiators, so they were respected and allowed to make decisions by their own judgment. They were allowed to stop fights completely or pause them for rest, refreshments, and rubdowns.

Victory or Death

Once the battle was decided, there were a few ways it could turn out. Some matches began with the understanding that the fight was to the death. Others might be decided in the heat of the moment. A gladiator could accept defeat by raising a finger in appeal to the referee. The editor would then decide whether the defeated person should die or not. If he decided the loser should live, it was called being granted missione. The editor would signal whether the gladiator was granted missione; he would turn his thumb up for missione granted, down for not. Usually, that decision is based on the crowd’s response, but ultimately the choice is the editor’s. The crowd’s favor depended a great deal on whether the gladiator was considered to have fought well. Bravery, skill, and genuine attempts to win were considered factors in fighting well. If a gladiator fought well, they would become popular, and the audience would want them to survive. In one instance, a gladiator with over 50 victories lost to another with around 20, and the audience spared him due his good fighting. Onrare occasions, emperors have popular fighters executed, which resulted in public outrage. On rare instances that there was a tie, the audience would decide the victor. Even more rarely, the editor would step in and kill the gladiator they deemed the loser.

In early battles, death was considered a righteous penalty for defeat, but that changed. Eventually, the demand for gladiators rose above the supply, so matches without missione were banned. This would change depending on the current emperor and their whims.

If a gladiator was not granted missione, he was to be killed by his opponent. It was expected that the gladiator would die well. To do so, the gladiator should never ask for mercy or cry out. A good death redeemed the gladiator from the weakness of their defeat, and they were considered noble by the audience.

Once the gladiator was dead, they would be placed on a couch and removed with dignity. They would be brought to the arena morgue, where the body was stripped of armor and their throat was cut to confirm their death. Another description of the morgue was that one arena official, dressed as the Roman god of the underworld, would strike the corpse with a mallet. Another worker dressed as a psychopomp god would test for signs of life with a heated rod. The mallet was considered a disgrace to those it struck. The bodies were thrown into rivers or dumped without proper burial.They would frequently be denied funeral rites. These gladiators would forever wander the earth as ghosts. Professional gladiators had their own separate cemeteries, especially if they had joined a union in life. These professionals could even have their victories and personal information engraved on crowns or wreaths. The graves of gladiators never claimed lack of skill to be the cause of death, but instead blamed Nemesis, fate, deception, or treachery. These graves made sure to prove that the gladiator was not responsible for his death and was worth avenging.

The winners of gladiatorial matches were rewarded heftily. First, they received a palm branch from the editor, which brought them honor. If they fought well enough, they could even receive a laurel crown or money from the crowd. They were also paid a large sum, and would be paid very well to return to the arena if they retired. For some, the reward was not money or fame, but freedom. For the slaves and criminals, the best reward was being set free. Their freedom was symbolized by the gift of a wooden training sword, called a rudis. In some rare circumstances, two gladiators could be evenly matched. If these two continued to fight bravely for a long time, and both accepted defeat at the same time, they could both receive victory and a rudis.You may also be interested in:

- Top 10 Most Powerful Gods in Greek Mythology (Ranked)

- 15 Most Frightening Greek Mythology Creatures

- Top 10 Best Greek Mythology Games

- Top 12 Gladiator Games Where You Fight to the Death

- [Top 15] Greek Mythology Monsters And What They're Famous For

- [Top 15] Greek Mythology Goddesses And What They're Famous For

- [Top 25] Best Greek Mythology Movies To Watch Right Now